A reflection on Dybala’s painful record: 800 days spent in the Infirmary, two years and three months lost without playing. Yet in his first three seasons at Palermo, Paulo never missed a match...

The Argentine’s troubles begin in the summer of 2015 with his move to Juventus, where in three months they add 3 kg of muscle mass to his frame. “Have you seen what thighs he has now?” says Allegri

(Translated into english by Grok)

When Paulo Dybala arrives in Italy, he is 18 years old. It’s July 20, 2012, when Maurizio Zamparini, president of Palermo, announces his signing from Instituto, a team in Argentina’s Primera B Nacional, where Paulo had played his last tournament earning an annual salary of 4,000 pesos—equivalent to 900 euros at the exchange rate, or 75 euros a month (the minimum wage in Argentina at the time).

Dybala stays at Palermo for three seasons, participating in three championships. The first is in Serie A, at 18 years old, where despite his young age he racks up 27 appearances and 3 goals; the second is in Serie B with 28 appearances and 5 goals; the third is back in Serie A with 34 appearances and 13 goals.

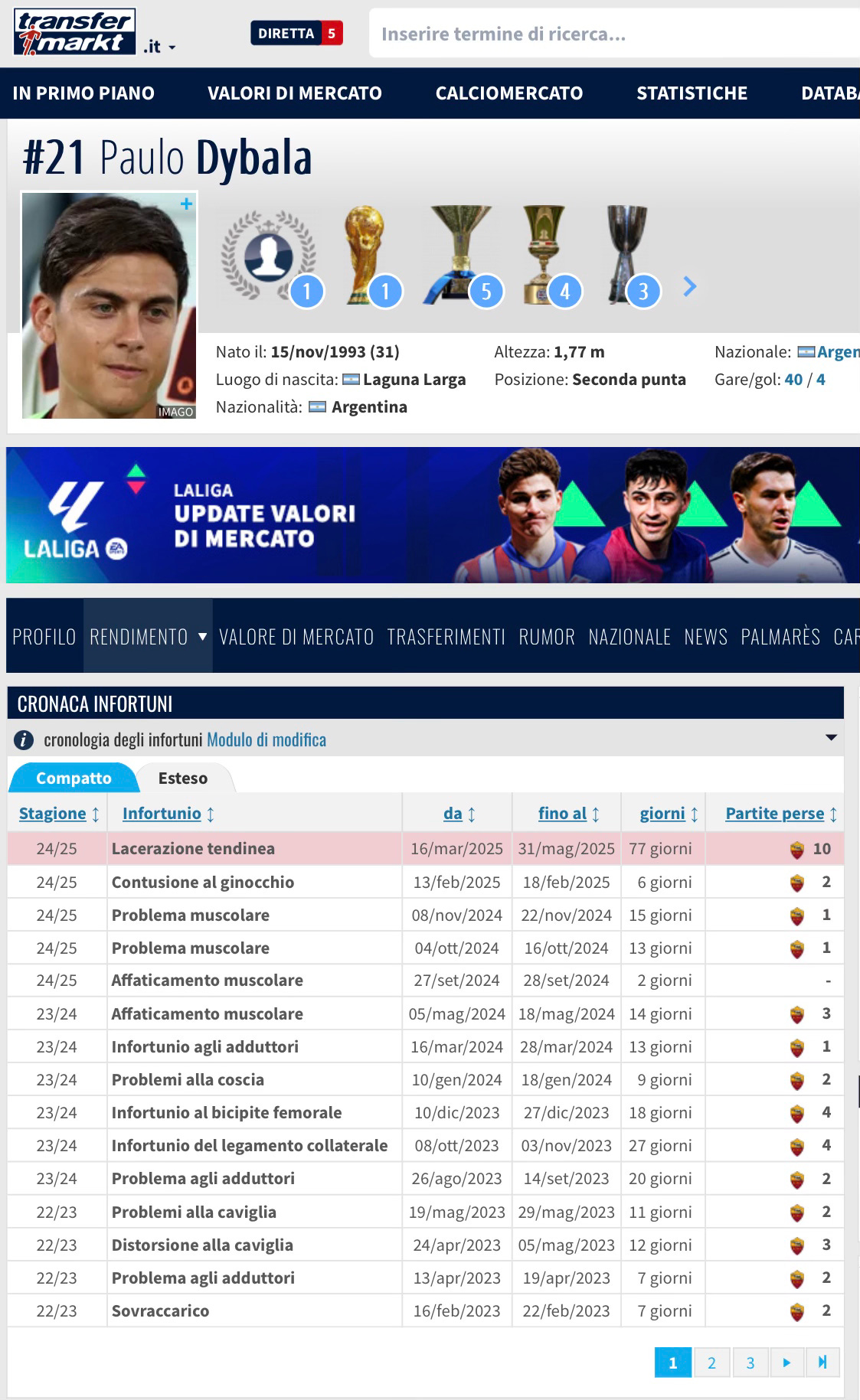

In those first three Italian years spent at Palermo, Paulo experiences the training methods of no fewer than five different coaches: Zamparini, in fact, changes coaches five times in three seasons—Sannino, Gasperini, Malesani (then Gasperini again, then Sannino again), Gattuso, and Iachini. Yet despite the constant shifts in methods and preparations, Dybala never suffers an injury. Transfermarkt, which dedicates a page to every player’s career injuries, records only a single “muscle problem” in his third season, keeping him out for four days, from January 12 to 15, 2015 (Monday to Thursday), without even causing him to miss a match.

Then, in the summer of 2015, Dybala moves to Juventus, who pay Palermo 32 million euros plus 8 million in bonuses: a total of 40 million, more than four times what Zamparini had spent to bring him from Instituto. Dybala is 21 years old. He’s over the moon because he feels his career is about to take off, but he doesn’t know (no one does) that alongside the joys, the pains will soon follow. If someone had told him his career was about to become a nightmare, he’d have told them to go to hell.

To be fair, it’s not as if Dybala didn’t achieve anything in his seven years at Juventus: 5 Serie A titles, 4 Italian Cups, and 3 Italian Super Cups are accomplishments that endure. And yet, there’s also that Transfermarkt record, on the injuries page—or rather, pages, because there are so many that three are needed. Pages that narrate an ordeal that has continued over the last three seasons at Roma, the most recent of which, still ongoing, ended prematurely a few days ago with an Achilles tendon injury suffered against Cagliari. This latest blow will force Paulo, after numerous long absences due to ligament injuries, into the operating room.

I said ordeal, and I wasn’t exaggerating. At 31 years old, Dybala’s medical record lists 35 injuries, almost all muscular, sustained throughout his career—injuries that have forced him to miss 125 matches (plus the 9 remaining in this season, bringing the total to 134) and spend a total of 758 days in the infirmary, a figure that will now easily surpass 800. For those who haven’t grasped it: 800 days of inactivity is more than two full calendar years—two years and a few months spent unable to practice your trade.

Out of curiosity, I checked how another striker of the same age (31) in our league, Napoli’s Lukaku, fares on Transfermarkt. Lukaku, a player who has certainly never shied away from effort in his career, has had 19 injuries—practically half of Dybala’s tally—and missed 73 matches compared to Dybala’s 134, again just over half. I then looked at two other leading strikers in their teams, Inter’s Lautaro and Milan’s Leao, who, granted, are younger: Lautaro is 27, Leao 25. Yet their injury records are standard: Lautaro has suffered 11 injuries, missing 16 matches, while Leao has had 9, slightly more serious (though no Serie A player stresses their muscle bands more than him), keeping him out for 30 matches. The disparity is so stark that the question arises naturally: what happened to Dybala, who at Palermo ran like a gazelle, never falling victim to injuries, when he moved to Juventus?

I had already tackled the Argentine’s drama here on Substack on September 15, 2023, in an article titled: “Juventus, Gazelles Turned into Bison,” with the subtitle: “If you arrive at Juve, within a few months you end up with a fearsome muscle mass: from Ibra to Dybala, from Bernardeschi to Bentancur, from Kean to Chiesa, all the (often harmful) transformations that unsettle.” In that piece, I documented, with interviews and newspaper clippings, the strange cases of players who, upon arriving at Juventus, admitted to changing their physique, weight, and build. Expressing my sorrow at seeing Paulo Dybala end up in an operating room yet again, with Roma now wondering whether to keep him or not, I’d like to revisit the most illuminating excerpts from that article I wrote two years ago. Sadly, it’s still relevant.

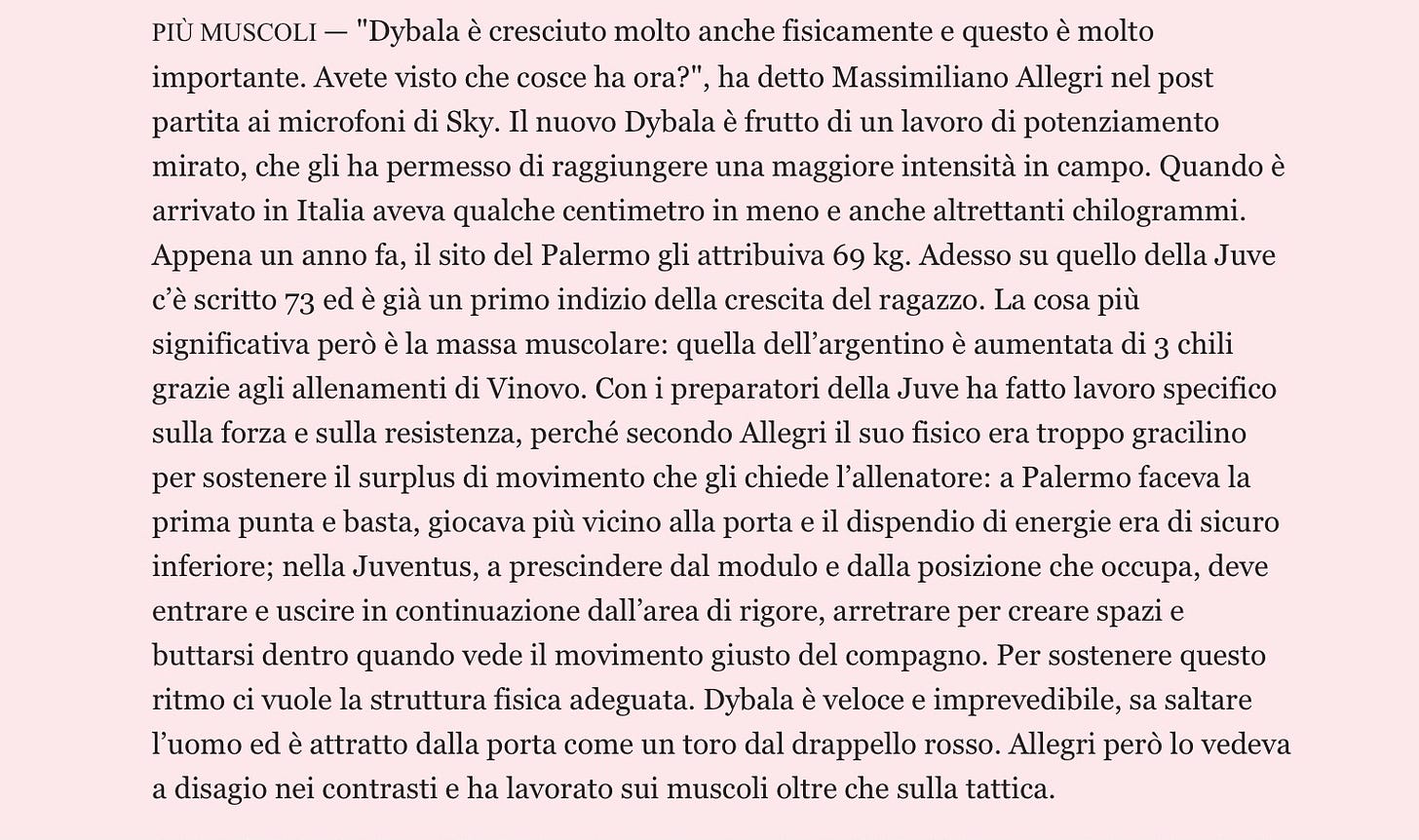

“[…] I was talking about Dybala yesterday: how last June he was a guest at Pogba’s house in Florida, during the days when it’s said Paul took a banned drug containing testosterone. I was talking about Dybala. And about the statement made by a beaming Massimiliano Allegri to Sky’s microphones on the night of Juventus-Milan 1-0, goal by Dybala, on November 21, 2015, his first season in the black-and-white jersey. ‘Dybala has grown a lot physically too, and that’s very important: have you seen what thighs he has now?’ This was followed by words from athletic trainer Roberto Sassi: ‘Significant physical work was done on Dybala, who, short and explosive in the first few meters, often couldn’t hold up to opponents’ physicality, negating his strengths. Paulo often ended his runs tasting the grass; by November, however, the specific work he undertook with the athletic staff prompted Allegri to say, “Dybala has grown a lot physically too. Have you seen how his legs have changed since he started working with us?”’.

In an interview with Il Nuovo Calcio, Sassi further explained: ‘One of the main tasks of preparation is to minimize the onset of muscle injuries. A key aspect of Juventus’s training is muscle focus. Through careful muscle recruitment—the activity of selecting, via targeted exercises, which muscle fibers to work—we train the fibers most stressed during matches, the so-called fast-twitch ones. These activate much faster (like when we make a sudden sprint) and release much more force than slow-twitch fibers. How are they trained? Through special machines, available at Vinovo, and targeted field exercises. Individual programs are designed to strengthen the relevant muscles, aiming to reduce the risk of overload, strains, or, worse, tears.’

Well, perhaps those special machines at Vinovo (and now at JMedical) weren’t so special after all; and the individualized programs and targeted exercises devised by Juventus’s trainers were poorly calibrated. Because, at least in Dybala’s case, who arrived as a gazelle and became a bison—no different from what happened to Del Piero, and others before him—the damage done is plain to see eight years later. Starting with Juventus’s decision to offload him last summer, deeming the management of a player constantly at risk of strains or tears no longer bearable. But what fault was it of Paulo Dybala’s? He was a gazelle that someone one day decided to turn into a bison, telling him it would keep him from getting hurt. ‘It’s madness,’ many protested. And it was.”

Uruguay’s Rodrigo Bentancur was also a gazelle when, at 20 years old, he arrived at Juventus from Boca Juniors in the summer of 2017. “Bentancur happy at Juventus: I’ve put on five kilos of muscle,” read the headline on October 11 from goal.com, which interviewed him three months after his arrival in the black-and-white jersey. And on December 21, a couple of months later, gazzetta.it reported: “Juve, Bentancur: I was slight, now I weigh 6 kilos more.” “It’s as if I’d done a year-and-a-half-long preparation,” the young man said in the interview. “I arrived very slight (even though he played at Boca, one of the world’s most prestigious clubs, which you’d assume knows how to train footballers, ed.), and now I’ve gained 6 kilos of muscle mass. I’ve improved a lot”.

Another gazelle turned into a bison, losing many of his technical qualities and gaining others as a workhorse—a role the football world is full of—was Federico Bernardeschi. In 2014, to snatch the 20-year-old from Fiorentina, Juventus paid Della Valle 40 million euros plus bonuses upfront. In 2019, sporting director Pierpaolo Marino, a veteran of Italian football management, told TuttoJuve.com: “His muscle growth impresses me a lot. He was quick, fast, not overly powerful. Now he’s different, he’s bulked up a lot, but in doing so, he’s altered his technical dynamics.” “He arrived at Juventus as an agile winger,” wrote footballnews24.it on the day of Bernardeschi’s farewell to the Old Lady, “and left this year heavier, with a completely different muscle structure.”

Yet another gazelle turned bison in the black-and-white jersey was Moise Kean. In the summer of 2021, with a sparkling start to the season, he seemed to have finally won over Massimiliano Allegri, who had never been entirely convinced of him. “But now it’s different,” explained Giovanni Kean, his brother, to the Juventus fan site ilbianconero.com. “He showed up to preseason in top shape and with more muscle mass”.

And what about Federico Chiesa, who, amid a thousand struggles, is trying to bounce back after rupturing his cruciate ligament in January 2022, but who, with every match, every sprint, keeps everyone (himself included) on edge as if the Sword of Damocles were hanging over his head? “Fans often point out that players at Juventus tend to gain muscle mass,” footballnews24.it wrote a year ago. “Players who arrive light and elegant bulk up with muscle, becoming stronger, yes, but also clumsier and less agile in their movements. Chiesa could become less dynamic and end up playing closer to the main striker.” Well, that’s exactly what’s happening now: Allegri now sees him as a pure forward, wants him to stay up top and score 15-16 goals. And yet, Chiesa was Chiesa: a one-of-a-kind talent. Why ask him to become Kean?

Players born as gazelles but immediately condemned, to survive, to become bison. It’s in this primordial stew that the case of Pogba testing positive for testosterone—a substance that increases muscle mass—simmered and eventually exploded, however things played out. The moral of the story: on Friday, October 5, counter-analyses will take place at Acqua Acetosa in Rome; I wish Pogba good luck, though it won’t change anything. But a doubt gnaws at me: aren’t we looking at the finger when we should be looking at the moon?