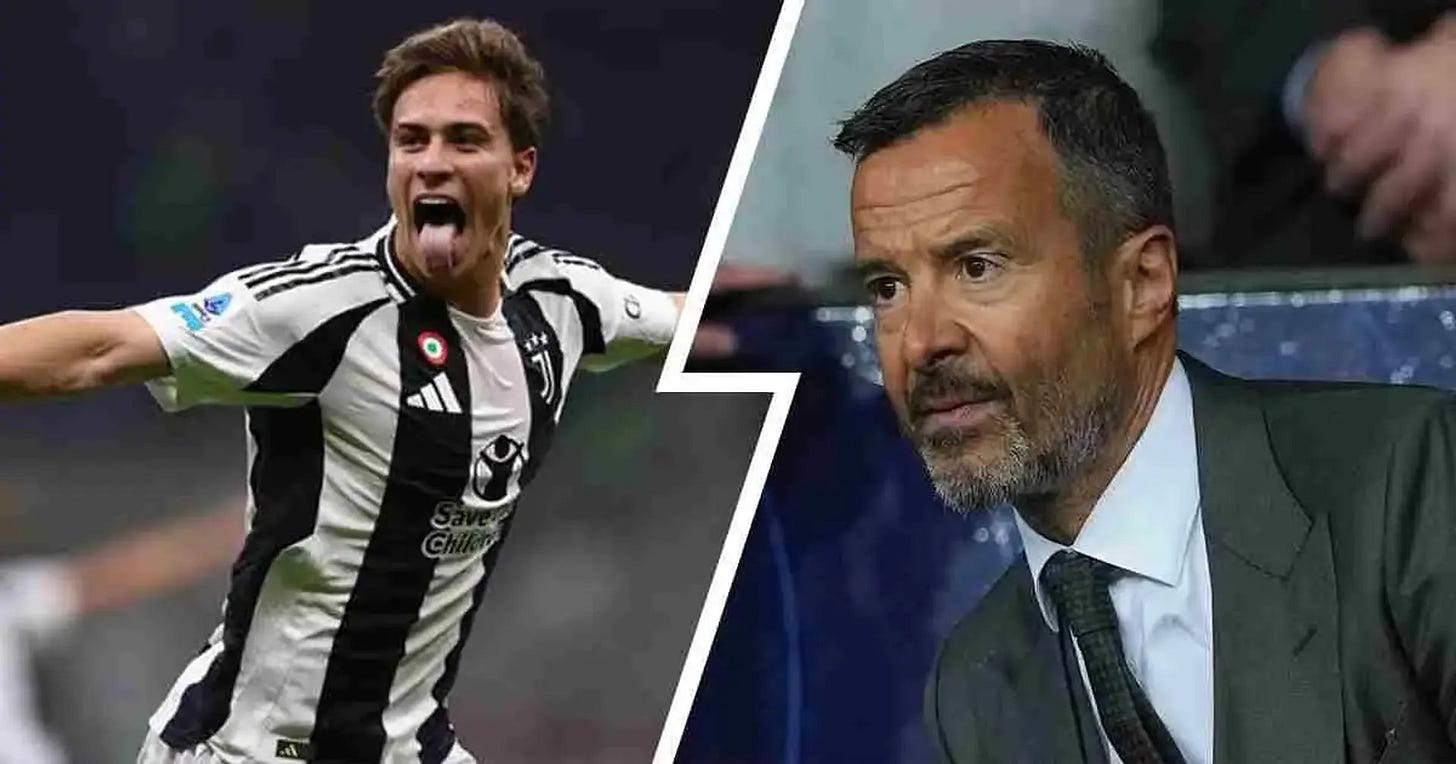

EXCLUSIVE: The 20 Days That Shook Juventus. Motta’s Undesirables: Vlahovic, Yildiz, Gatti, Cambiaso, Douglas. His Loyalists: Weah, McKennie, Thuram, Kelly, Locatelli, Nico, and Kolo Muani

An analysis of Motta’s moves, choices and words from the 3-5 defeat against Empoli to the 0-3 loss in Florence reveals how Thiago has played favorites, trusting only the working class.

(Translated into English by Grok)

Here’s the spoiler right away. Do you know which players Motta clung to during the toughest 20 days of his coaching career, deeming them—based on his personal reading of the squad—the most loyal and reliable? They are Weah, Kelly, Thuram, McKennie, Nico Gonzalez, and Kolo Muani, plus an addition, Locatelli. And do you know who, on the other hand, Motta distanced himself from, showing through his actions that he doesn’t consider them as loyal or reliable as he’d like? In strict alphabetical order, they are Cambiaso, Gatti, Perin, Vlahovic, and Yildiz, plus an addition, Douglas Luiz.

Caught in a sort of undefined limbo between the two camps is Koopmeiners.

If this were a movie, it could be titled “The Twenty Days That Shook Juventus”. To be more precise, nineteen days: the span between the evening of Wednesday, February 26—when Juventus lost 3-5 to Empoli in the Coppa Italia—and the afternoon of Sunday, March 16, when Fiorentina crushed Juventus 3-0. In less than three weeks, the Old Lady imploded in on herself, plunging her fans into the deepest dismay and leaving neutral observers and sports enthusiasts in utter disbelief. Nineteen days tied together by the red thread of four matches—Juventus-Empoli 2-3, Juventus-Verona 2-0, Juventus-Atalanta 0-4, and Fiorentina-Juventus 3-0—a crucial and revealing thread that serves today as Ariadne’s thread, guiding us back into the Bianconeri labyrinth in hopes of emerging, like Theseus, victorious. In our case—without Minotaurs to slay—victory means understanding, first by piecing them together and then cementing them, the thoughts that drove Thiago Motta to enact the behaviors, choices, and exclusions—unfortunately for Juve, losing ones—that led Madama to the disastrous collapse we’re witnessing.

Asking the question is important; getting the answers even more so. So: why did Motta make the choices he did? Which players did he try to hold onto during this 19-day trapeze leap without a net? And which ones did he lack faith in, marking a clear and sharp divide between himself and them, effectively sidelining them? If we hold tight to Ariadne’s thread and dive back into the heart of the Bianconeri labyrinth—where it all began on the night of Juventus-Empoli—and retrace the steps backward, all the answers come. Complete with the names of those Motta considered his soldiers and those he deemed, if not outright deserters, unfit for the cause. He made it explicit, if not to the media, certainly in the locker room: Motta has essentially played favorites, distancing himself from a group of players who, in his particular view, he didn’t and doesn’t believe can offer him the assurances that others did. Who does Motta trust? Not the ones who capture the collective imagination of fans and media, but the workhorses like McKennie, Weah, Kelly, Nico Gonzalez. Meanwhile, with the “big names”—from Vlahovic to Gatti, Yildiz to Cambiaso—Motta quickly felt he couldn’t rely on them, couldn’t trust them: he sensed them as distant, out of sync with his ideas. He loves the working class. And it’s indeed to the assembly-line workers that he turned during the 20 days that shook Juventus—only to come out battered and bruised.

You might be wondering: based on what complex and sophisticated reasoning did Ziliani identify the two factions—the “Motta loyalists” on one side and the “anti-Motta” players on the other? Or, if you prefer, the players Motta feels are “his” versus those he feels are distant? No flights of fancy: just deduction. But deduction grounded in the study and comparison of the four lineups fielded by the coach across the four stages of this painful Juventus Via Crucis. A comparison that, by analyzing promotions and demotions, says a lot.

Here are the four lineups: read them yourselves, then let’s reflect on them together.

JUVENTUS-EMPOLI 3-5

Perin;

Weah, Gatti, Kelly (then Locatelli), Cambiaso (then A. Costa);

Thuram, McKennie, Koopmeiners (then Yildiz);

Nico Gonzalez (then Conceição), Kolo Muani, Vlahovic.

JUVENTUS-VERONA 2-0

Di Gregorio;

Weah (then A. Costa), Gatti, Kelly (then Kalulu), Cambiaso;

Thuram, McKennie (then Koopmeiners), Locatelli;

Nico Gonzalez, Kolo Muani (then Vlahovic), Yildiz (then Mbangula).

JUVENTUS-ATALANTA 0-4

Di Gregorio;

Weah, Gatti (then Kalulu), Kelly (then A. Costa), Cambiaso;

Thuram, McKennie, Locatelli;

Nico Gonzalez (then Mbangula), Kolo Muani (then Vlahovic), Yildiz (then Koopmeiners).

FIORENTINA-JUVENTUS 3-0

Di Gregorio;

Weah (then Conceição), Kalulu, Veiga (then A. Costa), Kelly (then Gatti);

Thuram, McKennie, Locatelli;

Koopmeiners, Kolo Muani, Nico Gonzalez (then Cambiaso, then Mbangula).

As you may have noticed, I’ve bolded certain names in each lineup: there are six of them, and they reveal the first undeniable truth about the moves Motta made during the 20 days that shook Juventus. After the harsh and unusual j’accuse he delivered on TV following the Coppa Italia sinking against Empoli—an open indictment of players who had caused him “shame” alongside millions of fans—he identified six of them as the ones he’d rely on to try to bring the sunken battleship back to the surface. The six bolded names are the six players the coach never wanted to do without across all four matches of his Calvary. And surprisingly (though perhaps not, knowing Motta), the six loyalists he wanted by his side are six foot soldiers: Weah and Kelly in defense, Thuram and McKennie in midfield, Nico Gonzalez and Kolo Muani in attack, all starting from the first minute in all four games. Yes, I agree that calling Kolo Muani a foot soldier might be a stretch—but it’s far less so when you see who Motta sacrificed and sidelined to make room for him: the highest-paid player in Serie A, the monstrous €91.6 million investment, the striker who arrived in 2022 as the poster boy for Juventus’ future, Dusan Vlahovic.

To those six names, a seventh must be added: Locatelli. He wasn’t among the starting eleven in the first match of this quadrilogy (or tetralogy, if you prefer), Juventus-Empoli 3-5; but after the shipwreck, Motta immediately reinstated him, clearly feeling his need and never benching him again. So, for Motta, these are the “magnificent seven”: Weah, Kelly, Thuram, McKennie, Locatelli, Nico Gonzalez, Kolo Muani. Let’s be honest: not exactly the names that ignite the fantasies and excitement of fans.

The ones who spark the imagination of the masses, you’ll agree, are—each for different reasons—Yildiz and Gatti, Vlahovic and Cambiaso. And if you asked fans whether they have more room in their hearts for Di Gregorio or Perin, nine out of ten would say Perin. Well, if you go back and listen to the words Motta uttered in his ruthless j’accuse after Juventus-Empoli, one of the phrases that struck me most was: “We need to realize that we have to earn the right to be here every day. We can’t demand without giving.” Demand without giving. Who at Juventus had demanded something without delivering, prompting the coach to put them back in line? Certainly Vlahovic, who, from the national team camp, had once said he preferred a two-striker attack, like with Serbia, rather than a lone striker role, as at Juve—and against Empoli, he was indulged, starting alongside Kolo Muani from minute one, yet he failed to make an impact and even missed his shot in the final penalty shootout. Certainly Yildiz, who, after a surprise meeting a few days earlier with Jorge Mendes—offering him astronomical contract proposals from other European clubs—seemed distracted to Motta, so much so that the coach didn’t hesitate to drop him from the squad.

Certainly Cambiaso, who, enchanted by transfer rumors of Manchester City willing to spend €70 million to gift him to Guardiola (Italian papers genuinely wrote this throughout January) and disheartened by not even receiving a €30 million offer, grew melancholic both off and on the pitch, starting to cause damage—so Motta gave him the same fate as Yildiz.

In a big club, there have always been patricians and plebeians: the trick is making them coexist. But Motta has a minimal tolerance threshold for the former and a clear preference for the latter. The ones who don’t get big-headed like Vlahovic, Yildiz, or Cambiaso—or even Gatti, who, after receiving the captain’s armband at the season’s start, didn’t respond, in the coach’s view, with the required attitude and behavior. So, go back and look at the four lineups of Juventus’ tetralogy: you’ll see six workers always on the pitch from the first minute of every game, and Vlahovic disappearing after the Empoli debacle, Yildiz, Cambiaso, and Gatti vanishing after the Atalanta shipwreck—deemed by Motta the most culpable. The plebeians were spared; the patricians were sentenced to death. Oh, and I forgot: after Empoli, Perin was out too. For Motta, the more disciplined, quiet, and non-“Allegri-esque” Di Gregorio was preferable.

Between the “loyal” and the “disloyal,” the one who disappears and reappears on the radar is Koopmeiners. Motta loved him at Atalanta, seeing in him a “plebeian star,” a champion who blossomed in the provinces after a tough life as a workhorse midfielder. Too bad that, once in Turin, under the spotlight, the Dutchman melted like snow in the sun—to Motta’s despair, as he genuinely thought he could make him the permanent center of gravity for his Juventus. Instead, that center of gravity—far more modestly, despite all his limitations—has become Locatelli. And the only thing permanent at Juve is the wait to see Koopmeiners play a game that’s not just good, but at least decent. Though he’s the player Motta loved (and waited for) the most, the waiting time is up. For him, too, it’s now do or die. The trouble is that when he’s in, it’s as if he’s out—nowhere to be found.

As for Conceição, whom Motta considers marginal and prefers Mbangula over—appreciating the latter’s demeanor, discipline, and humbler origins—and Douglas Luiz, whom Motta likes as much as a princess likes a pea under her mattress, and Kalulu, who instead has all the makings to join the ranks of Motta’s “loyalists,” we’re left to wonder whether this holy war Motta unleashed within his own locker room—fought silently between the obedient and the disobedient, the dutiful and the resentful, the humble and the haughty—has done Juventus any good. Motta’s mistake, having worked only with foot soldiers at Genoa, Spezia, and Bologna—turning some, through his and their skill, into minor stars (Calafiori, Zirkzee, Ferguson, even Saelemaekers)—was coming to Juventus and wanting to reset everything, even the team’s hierarchy, to start anew with an “everyone is equal” approach: no champions, only foot soldiers. It was a colossal blunder. Weah and Yildiz, McKennie and Vlahovic, Kelly and Gatti should have been blended together, highlighting their differences, not flattened by erasing them. Especially since Giuntoli had already lowered the overall quality bar by buying players who were little more than average and passing them off as champions.

Here’s the thing: Koopmeiners, Douglas Luiz, and Nico Gonzalez—the three big coups of Cristiano Giuntoli—are today the emblem of the new Juventus. A top club where champions are unwelcome, both to the coach, who sidelines them, and to the sporting director, who can’t spot them and buys knockoffs instead. The Working Class Goes to Paradise, as the famous Elio Petri film was titled. At Juve, though, it’s ended up in hell.