The Scandal nobody talked about: the 718,000 euro FIGC-Juventus plea bargain that recidivism from the capital gains trial made impossible

In June 2023, Juventus had to answer for four offenses violating Article 4: the same article for which it had just been convicted. Recidivism prohibited the plea bargain, and yet...

(Translated into English by Grok)

The plea bargain request made to the Rome Prosecutor's Office by Juventus’ lawyers (and thus those of Agnelli, Paratici, Nedved, and other involved executives) to avoid the trial in the Prisma investigation and put an end to the biggest Italian football scandal since Calciopoli—once again starring Juventus—brings attention back to the nature of this particular procedure in Italian criminal law, namely the plea bargain. With a plea bargain, or “application of the penalty upon the parties’ request,” the defendant and the public prosecutor agree on a penalty that the judge may then reduce by up to one-third. The agreement, in addition to a reduced sentence for the defendant, allows for an early resolution of the case, avoiding the lengthy trial process.

Just as in criminal law, the plea bargain is also provided for in sports law. In recent times, we’ve seen it used frequently and in the most diverse contexts: starting with the FIGC-Juventus collusion (May 30, 2023), which, in exchange for a 718,000-euro fine, allowed the Bianconeri to escape a maxi-trial where they would have had to answer for four serious and distinct offenses, avoiding a relegation that seemed certain; and then in the case of national team players Fagioli and Tonali, implicated in the betting scandal; in the case of the blasphemy uttered by Inter’s captain Lautaro Martinez; in the case of improper relations with criminal fans by Inter’s Simone Inzaghi and Hakan Calhanoglu, and so on.

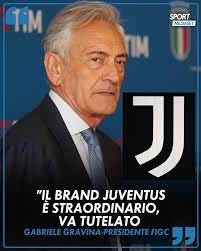

Since Italian sports justice is a farce, everyone now resorts to plea bargaining: you could have committed the most heinous of misdeeds, but if you have the right “brand”—to use Gravina’s words—you can be sure you’ll get off with a slap on the wrist. However, there’s something not everyone knows: plea bargaining is not always allowed. The first case of prohibition cited in the Sports Justice Code is “recidivism”: if the accused has already committed a violation of the same type as the one now charged, no plea bargain is permitted. If you’re accused of stealing apples and pears and request a plea bargain, you can’t have it if you’ve already been investigated, tried, and convicted for stealing apples and pears in the past. There’s recidivism. Clear and simple, right?

Well, do you know what happened two years ago when Juventus and the FIGC Prosecutor’s Office agreed on the shameful plea bargain, the one with the 718,000-euro fine that erased years of offenses committed by the Bianconeri, offenses proven beyond any reasonable doubt? The plea bargain shouldn’t even have been discussed by the Federal Prosecutor’s Office: precisely because of the recidivism impediment. A few months earlier, Juventus had been charged, tried, and definitively convicted in the capital gains trial for violating Article 4—the same article for whose violation Juventus was now charged by the FIGC Prosecutor’s Office to answer for four offenses: salary maneuver 1, salary maneuver 2, friendly clubs, and colluding agents. Juventus had already committed similar violations (it had even been judged and definitively convicted): ergo, no plea bargain was possible.

And yet, you know that when there’s an “extraordinary brand” to save, FIGC President Gravina doesn’t care about anyone, let alone the regulations.

So, Prosecutor Chinè, blessed from above, after “discussing”—so to speak—with Juventus’ lawyers, said yes to a plea bargain that, in exchange for a laughable fine, would spare the Bianconeri from the maxi-trial. He then knocked on the door of the CONI General Prosecutor’s Office to get its approval. Incredibly but true, the Prosecutor’s Office sent both Chinè and the Old Lady packing: Juventus must answer today for violating Article 4, it said, the same article for whose violation it was tried and convicted a few months ago in the capital gains trial. There’s recidivism. And no plea bargain is allowed.

But you can’t outsmart the FIGC so easily. And so, after repeated late-night summits in the Palace of His Eminence Gabriele Gravina, slowly but surely—tomo tomo, cacchio cacchio, as Totò would say—Prosecutor Chinè showed up one morning, arm in arm with Juventus’ lawyers, at the door of the National Federal Court, where the maxi-trial against Madama was soon to take place. “We’ve agreed on a plea bargain,” Chinè says to the person who opens the door, namely the Court President Carlo Sica, “would you be so kind as to read and approve it?”

“Gladly,” replies Sica. He finds it perfect, signs it, and countersigns it, effectively killing the maxi-trial that would have sent Juventus, with the judges’ leniency, to Serie B, or otherwise to Serie D. Recidivism? What’s that? The regulations? Nowhere to be found. The appropriateness of the penalty? Trifles, quibbles, pinzillacchere, as Totò would say.

Five months later, on November 1, 2023, in an article written for my “Poisoned Ball” account titled: “All the ‘sons of’ that Gravina hired in FIGC: Giorgetti, Tajani, and also Sica, the judge who blessed the Juventus plea bargain”, among other things, I wrote:

“…after all, Gravina has never denied a job to an ‘excellent son.’ Not to politicians, not to friends, or to those who have proven themselves to be friends in deeds. Take Carlo Sica, former Deputy State Attorney General, the man who, on May 30, as president of the FIGC’s National Federal Court, did not hesitate to give his approval—and bless as valid—the plea bargain agreed upon between the FIGC Prosecutor’s Office and Juventus, an agreement that allowed the Bianconeri, in exchange for a 718,000-euro fine, to escape a trial for an endless series of offenses committed and proven beyond any reasonable doubt, a trial that would have resulted in Juventus’ relegation to Serie B or C (consider that for the capital gains offense alone, Madama received a 10-point deduction in Italy and was later expelled from all European competitions).

Despite the plea bargain being, by regulation, not even proposable due to the recidivism impediment (Juventus had already been charged, tried, and convicted for violating Article 4, the same article contested for all the offenses in the ‘salary maneuvers’ case), and despite the agreed sanction between the parties, FIGC and Juventus, appearing entirely incongruous and inadequate given the severity, repetitiveness, and pervasiveness of the crimes committed by Agnelli and company, the Federal Court President Sica decided that it wasn’t a collusion: ‘The National Federal Court – Disciplinary Section, presided over by Carlo Sica, having reviewed the proposed agreement, pursuant to Article 127 CGS, declares it effective.’ This is what the statement of what can be called the scandal of scandals in Italian football history reads. As they say in these cases: ‘pay cash (read: a ridiculous fine), get a camel (read: a complete pardon).’

And so, how could the FIGC deny a job to the son of Federal Court President Sica? It couldn’t. And so, here’s Emanuele Sica, son of Carlo Sica, hired by President Gravina at Club Italia, the modern-day Sarchiapone, with a contract that, in record time, went from fixed-term to permanent. Forever and ever, until retirement, with gratitude and appreciation. Amen.”

Did you enjoy the tale of “Madama in the Land of Plea Bargains”? I loved it.

Too bad it’s not a fairy tale.