When 19 years ago, around these days, Calciopoli broke out: from the first whisper in Gazzetta to the bombshell of the interceptions, the two weeks that shook football

On Saturday, April 22, 2006, the deputy editor of Gazzetta foreshadows a "hot summer" for football; on May 4, the first interceptions are published. I tell the full story in the book "Rigged Football"

(Translated into English by Grok)

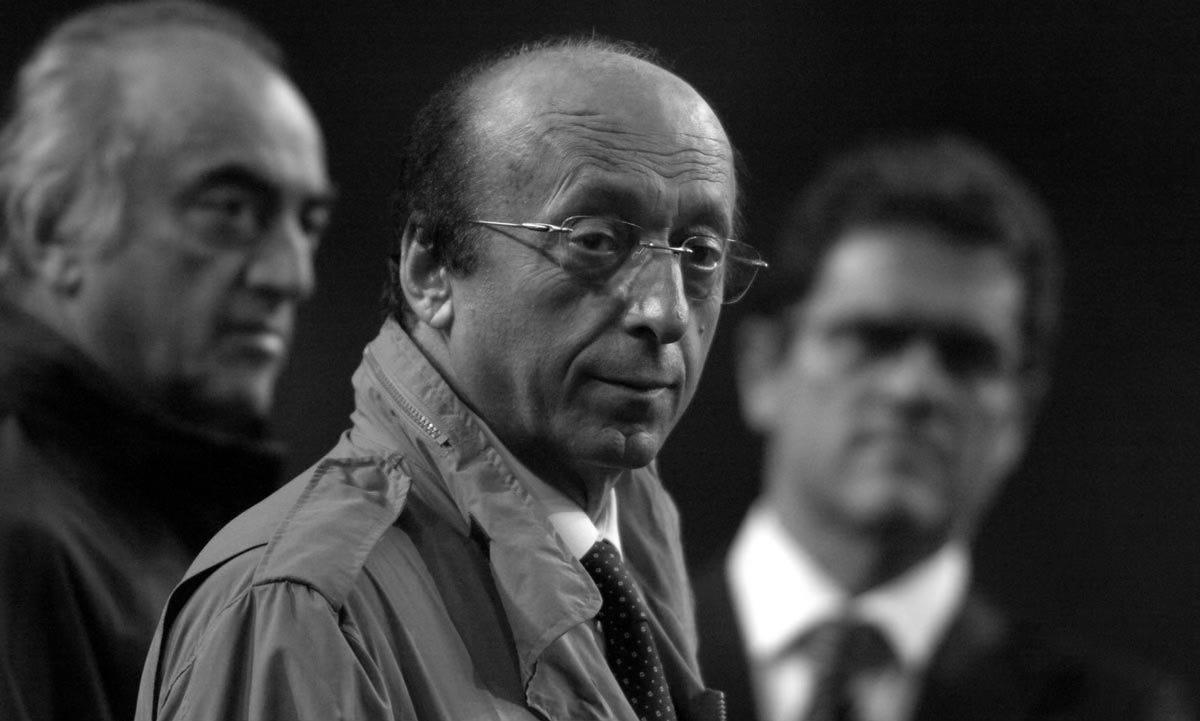

Many of you, especially the younger ones, may not remember: it was precisely in these days, between late April and early May, 19 years ago, that the Calciopoli scandal exploded and erupted with all its devastating force. For years, perhaps decades, we had witnessed completely rigged championships; only the fools and the sycophants didn’t notice (or pretended not to) until one fine day, the foul-smelling cesspool of Italian football, with its worm—the criminal "Cupola" led by Luciano Moggi and his band, based at Juventus and with roots everywhere—was brought to light. The shock was absolute: everyone realized that the rot in Italian football was ubiquitous, lurking in the Federation, among referees, and even in newspapers and TV, and that the corruption was total, surpassing even the most pessimistic and imaginative expectations.

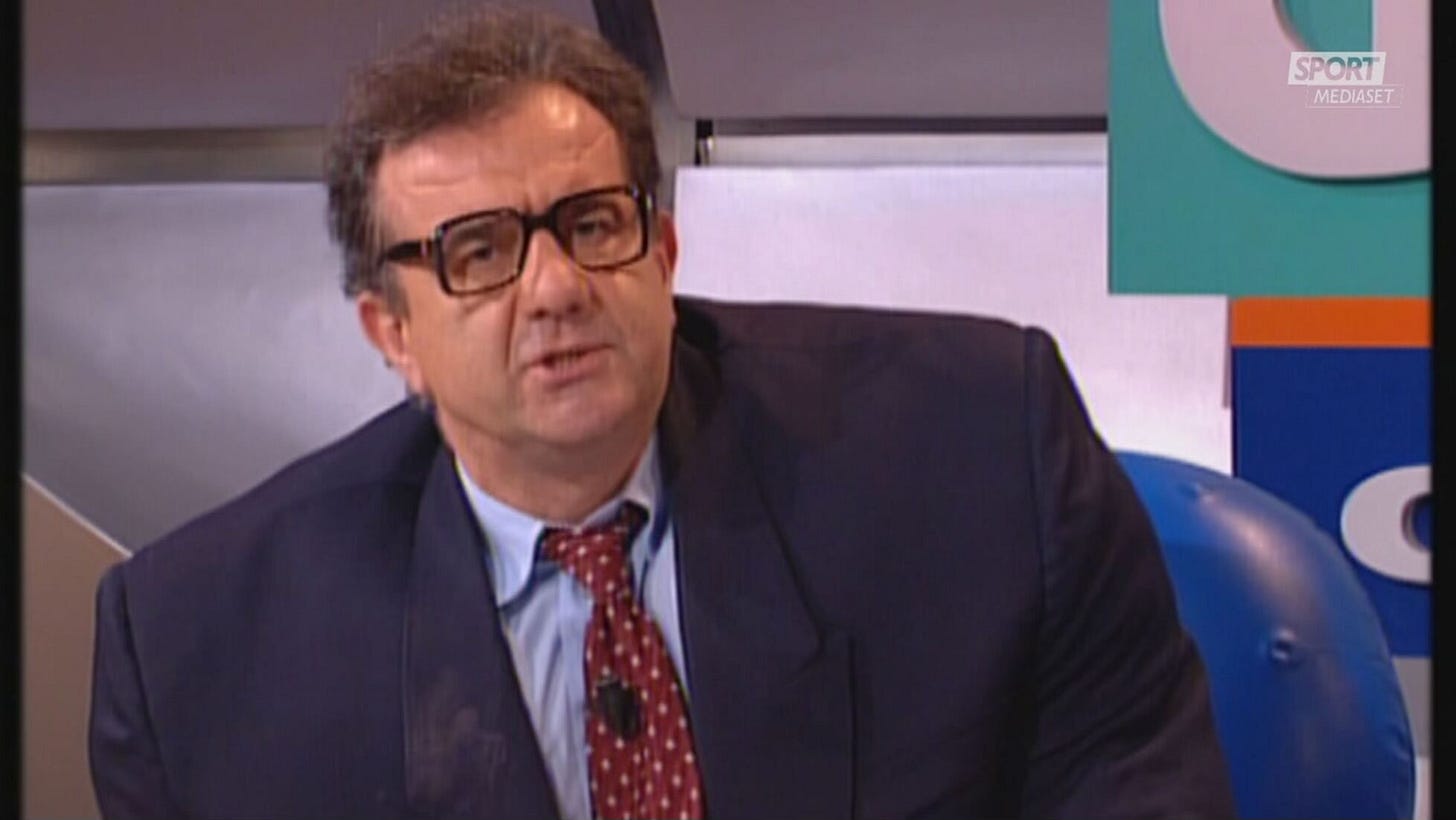

At the time, I was working in Mediaset’s sports editorial team and was the author and curator of two programs: Controcampo and Guida al Campionato. For Controcampo, I also wrote the match report cards for the Sunday evening game; on several occasions, I came across Juventus matches officiated in a shameful manner, such as Bologna-Juventus 0-1, 2004-05, refereed by Pieri, which in my opinion set the record for disgrace, alongside Juventus-Inter 1-0, refereed by Ceccarini, the infamous Iuliano-Ronaldo penalty/non-penalty incident of April ’98. As much as I could, I was very direct and harsh in commenting on the events I was tasked with covering for work; it’s no coincidence that I was the target of numerous lawsuits from the refereeing and federation world. I also recall one day, for a skit co-written with Gene Gnocchi and aired on Guida al Campionato, where Gene imitated Moggi, portraying his gestures and behavior in the style of a mafia boss, Juventus immediately halted sending their players to Mediaset programs, starting with that evening’s Controcampo. It took a month to smooth things over, with Juventus demanding the destruction of every copy of the offending episode.

As the journalist who had most actively denounced the still-hidden distortions and shames of the Italian championship, Ettore Rognoni, the sports director, asked me to write an instant book to be sold with the weekly magazine Controcampo. I wrote it at breakneck speed, in a few days and nights, as the scandal grew larger by the day. We titled the book Rigged Football. What I’m sharing today are the opening pages, the introduction.

2006: Odyssey in Agony

It all begins in a far from romantic way. If in All the President’s Men, the film about the Watergate scandal, a radiant Robert Redford sits behind an elegant lawyer in a courtroom and, startling him, whispers, “I’m Bob Woodward from the Washington Post. Are you here for the Watergate break-in?”, the first scene of the scandal that rocked Italian football has nothing adventurous or alluring about it. In fact, it’s such an unappealing flash that no one, not even those in the industry, seems to notice anything.

Flashback. It’s Saturday, April 22, 2006, and Gazzetta dello Sport hits the newsstands, publishing, on the third-to-last page, the column by one of its deputy editors, Ruggiero Palombo: in the photo embedded in the header, he tries to look reassuring, but in a comparison with Robert Redford—aka Bob Woodward—he loses 3-0. Palombo’s column, titled “Glass Palace,” deals week after week with the generally tedious squabbles that have always plagued the football establishment. Palombo won’t take offense if we say that his column is usually skipped by 9 out of 10 readers, and even industry insiders, when approaching it, sometimes experience a widespread sense of drowsiness.

Be that as it may, this is how it all begins. On page 36 of Gazzetta dello Sport, next to the readers’ letters, on the morning of that Saturday, April 22, Ruggiero Palombo signs an article titled: “Football’s Ricucci, Beware the Summer.” Not exactly a bombshell headline; and indeed, the piece goes unnoticed by most, including sports journalists. Not a single reporter, in a newspaper or TV newsroom, looks up from the paper and says to the colleague at the next desk, “Hey, did you read Palombo’s piece in the pink paper?”

By Ruggiero Palombo

“Italy is the land of phone taps. The banking world knows this well—ask Fazio, Consorte, Fiorani, and all those involved in various ways in the more or less notorious affairs of recent months. Stefano Ricucci, the super Lazio fan entrepreneur who, due to a few too many recorded phone calls, has been locked up in Rome’s Regina Coeli prison since last Tuesday, knows it too.

For now, sport has remained on the sidelines of these embarrassing situations (…) But what could happen if, perhaps after the championship ends, in the calm before the great World Cup spectacle, some hefty dossiers were to emerge, recounting this or that phone call, revealing how football lived its daily life—not a century ago, but just a year ago? Let’s be clear, it’s not necessarily about uncovering some stinking pot or discovering actual sports crimes. A ‘snapshot’ of a certain way of living football among prestigious industry figures might be enough (and more than enough) to make the upcoming summer scorching hot.

Fantasy football? Just in case, we suggest that the Federation and CONI prepare for any eventuality. It would indeed be unfortunate to discover that everyone knew everything. And that no one had moved (beyond the bare minimum) in the hope that certain misdeeds would remain locked in some prosecutor’s drawer. In certain circumstances, opening the windows can be far more useful than stubbornly keeping them shut.

P.S. A word to the wise: from now on, instead of sneaky cell phones, we suggest a return to the good old ‘pizzini’ (handwritten notes).” (April 22, 2006)

Less than two weeks later, on May 4, the bomb goes off.

The sludge that came to light is unimaginable. Among the first reports published by newspapers that May 4, after the release of the initial interceptions, Marco Travaglio’s stands out, as he was writing for l’Unità at the time.

By Marco Travaglio

There’s the folklore: Luciano Moggi calls Aldo Biscardi (“love,” “angel”), the journalist reminds him of a bet won and never paid, so the Juventus general manager is forced to remind him that he already settled it with “a 40-million-lire watch.” There’s the conflict of interest with Alessandro Moggi, the son, who, through his agency Gea, moves players left and right with the loving help and advice of dad Luciano in his triple role as father, Juventus GM, and orchestrator of a large slice of the football market. There’s the military control over referee designators: on one side, Pierluigi Pairetto, whom Moggi calls “Pinochet” on the phone; on the other, Paolo Bergamo, dubbed “Atalanta.” There are the executives of the institutions, FIGC and UEFA, bent to serve partisan interests: to favor friends and, above all, to secure friendly referees, in the league (partial draw with the so-called grids) and in the Champions League (direct designation). There’s even a meeting at Antonio Giraudo’s house, Juventus CEO, with Lucianone and the two designators. There’s a bit of everything, in short, in the phone taps ordered by the Turin Prosecutor’s Office between August 10 and September 27, 2004, as part of a (later closed) case against Moggi, Giraudo, and Pairetto for criminal association aimed at sports fraud, now on the desks of FIGC, UEFA, and the Rome Prosecutor’s Office. The undisputed star: Luciano Moggi.

MOGGI THE DESIGNATOR - On August 10, 2004, the first leg of the Champions League preliminary round is played in Turin between Juventus and Sweden’s Djurgarden. German referee Herbert Fandel disallows a goal by Miccoli, and it ends 2-2. The next day, Moggi calls Pairetto: “Gigi, what the hell kind of referee did you send us?” Pairetto tries to defend him: “Fandel is one of the best, the top.” Moggi: “He can go to hell, I’m telling you. Oh, and make sure for Stockholm (the return leg), eh?” Pairetto: “Holy cow, my goodness, this one really has to be a match…” While he’s at it, Lucianone gives instructions for a friendly in Messina: “Oh, in Messina, send me Consolo and Battaglia. With Cassarà, eh?” Pairetto: “Already done.” For the friendly in Livorno, everything’s set too. Moggi: “In Livorno, Rocchi, eh?” Pairetto: “In Livorno, Rocchi, yes.” A thought for the big August match against Milan, the Luigi Berlusconi Trophy. There, too, Moggi picks the referee: “And for the ‘Berlusconi,’ Pieri, make sure.” Pairetto: “We haven’t done it yet.” Moggi: “We’ll do it later, come on.” Sure enough, on August 27, the referee at the Meazza will be Pieri. “With Gigi (Pairetto), it’s a blast,” Moggi boasts to Giraudo: the friendly designator just called from UEFA, announcing a great referee for the Champions League return leg: “Pinochet told me it’s Cardoso, he’s good.” But then, unexpectedly, it’s the Englishman Graham Poll (Moggi calls him “Paul Green”): “They changed the referee, damn them. What the hell, I want to hear from them today.” He calls Pairetto: “What about Cardoso, eh?” The designator is embarrassed: “Something happened at the last minute, I had Cardoso; something must have gone wrong.” It all works out: 4-1 away against Djurgarden, Juventus qualifies.

THE KNIGHT’S COMB - At the Berlusconi Trophy, after the match, Prime Minister Berlusconi organizes a dinner with Galliani, Giraudo, referee Pieri, and other VIPs. The next day, Giraudo calls Moggi: “Berlusconi and Galliani went to the table with Pieri, so I went too, I shadowed them.” But the best part happened in the locker rooms, where, Moggi recounts, amused: “Berlusconi took the comb and combed ‘Pinochet’ with his own comb. The results don’t matter much, heh heh.” Indeed, Pairetto continues to be a “blast.” On September 1, he calls Moggi: “I’ve put a great referee for the Amsterdam match: Majer.” Moggi: “Awesome, come on!” Pairetto: “See, I remember you, even if you’ve forgotten about me by now.” Moggi: “Don’t be a pain, you’ll see when I’m back, I’ll tell you if I’ve forgotten.”

FATHER AND SON - Alessandro Moggi discusses with his dad the fate of players like Cristiano Zanetti, Galante, Chiellini, Zalayeta, Salas, Jankulovski, as well as agents Terraneo and Perinetti. Moggi Jr. offers Moggi Sr. Lazio’s Liverani. But for Luciano, he’s “too slow,” while “Baiocco could be considered.” The two are very interested in Napoli, halfway between Udinese president Pozzo and producer De Laurentiis. On August 28, 2004, father and son discuss the Miccoli deal with Lazio. Luciano: “I asked Lotito for 10 million, and he said 5, right? You need to tell him: look, I can convince my dad to do it for 7.5. Make a bit of a fuss at first.” Ale, who manages Miccoli, takes note. But Miccoli is being difficult. Moggi Sr. calls a friend to tell him “to stop acting stupid,” otherwise “I won’t let him get called up to the national team, that’ll teach him, because I’m the one who got him into the national team.”

A BLONDE AT RISK - Amid the grand games of Italian football, there’s also time for more mundane matters, like the placement of a CAN (National Referees Commission) official who works with the two designators. She’s very close to Bergamo, a friend of Moggi, but disliked by Pairetto after she badmouthed him (“after what she’s said about me,” Gigi thunders, “I don’t want her anymore, a snake in the grass”). She needs to be parachuted into another office, but without upsetting her, as she holds many secrets. Who steps in to handle this little state affair? Moggi, of course. On September 1, he calls Franco Carraro. He starts indirectly, talking about Napoli’s fate, now in De Laurentiis’s hands (Carraro: “He’s completely crazy,” Moggi: “They’re all crazy there, but I’ll have a chat with him soon”). Then he casually mentions that the new national team coach, Marcello Lippi, needs to be “kept in check, straightened out.” How? “By setting up an office for him with a secretary, someone who knows international referees.”

Here’s the thing: he has just the person in mind, “that blonde, ambitious one, who knows the whole scene.” A certain G. F. (Grazia Fazi). Moggi discusses her with Carraro’s deputy, Innocenzo Mazzini, his loyal ally. Mazzini gets the hint: “You’ve got some nerve, you dirty dog, eh?” Moggi admits the reason for the transfer: “She needs to be removed from where she is.” Mazzini: “The blonde’s going around saying they’ve brought in lawyers, and if they don’t give her everything, she’ll cause a huge mess, a real scandal.” Moggi, cautious: “I don’t know what she’s done there, but let’s not talk about it on the phone.” Mazzini: “You told me you had no control.” Moggi has a hunch: “What do I know about what they’re up to?” The important thing is to keep Carraro in the dark about the backstory: “He,” Moggi insists, “mustn’t know; he knows nothing about the mechanism.” Lippi, however, resists. And Bergamo defends “the blonde.” Mazzini fears blackmail: “She wants a big career, otherwise she’ll spill to the papers.” Moggi slams his fists: if the two designators keep fighting, “I’ll go to Carraro and have them both kicked out. If they piss me off, the inseparable duo goes home early.” In fact, “I’ll have Bergamo sacked.” As if the designators were his property. Mazzini, terrified: “Be careful with the papers, they know everything, she’s covered herself, and if she opens her mouth…” In the end, G. F. was moved from the CAN to another FIGC office.

DINNER AT GIRAUDO’S - All’s well that ends well, except for poor designator Bergamo, chewed out by Carraro in front of everyone at the September 17 meeting. Moggi laughs about it with Giraudo: “He gave ‘Atalanta’ a hell of a scolding, he’s totally guilty!” Then he calls Bergamo to cheer him up: “Come to dinner at Giraudo’s on Tuesday? I need to tell you what Carraro said; he’s really got it in for you.” Bergamo is still “furious” with the president for “how he treated me, he stripped me of respect.” He’s plotting revenge: “I’ll make him pay, I don’t know how much longer I can take it, I’ll make him look so bad in the papers he’ll be ashamed for life.” Moggi tries to calm him: “Stay cool, I’ve talked to him, it’s over, come on. I’ll fix it, don’t worry, I’ve already sorted everything. Let’s meet Tuesday at 7:30 at Antonio’s.” The dinner takes place on Tuesday, September 21, the eve of Sampdoria-Juventus. It seems Pairetto attends too: at 10:36 PM, he calls his son (Moggi’s voice can be heard in the background) to have him read “the Saturday-Sunday schedule,” the fourth matchday. Clearly, the two designators are discussing it with Juventus’s top brass. For what purpose, we’ll never know: a few days later, the interceptions stop. (May 4, 2006)